The Baldwin Hall Controversy

Introduction

In 1998, DNA tests all-but proved that Thomas Jefferson had fathered children by Sally Hemings, the enslaved, teen-aged, half-sister of his wife. Ample evidence long supported this fact, but a single DNA kit put to rest two hundred years of denial by white historians who claimed that Jefferson’s black descendants, with all their documentation and faithful histories, were liars.

In 2016, a similar drama played out in Athens, Georgia. Oral histories and historical evidence supported the notion that the University of Georgia’s Baldwin Hall had been erected on the graves of the city’s enslaved community. What was commonly understood in the black community, however, was denied, obfuscated, or misremembered by too many in the white community.

The Department will maintain this publicly available chronicle of Baldwin Hall, updating it as new information comes to light, so that this history cannot again be forgotten.

The Past

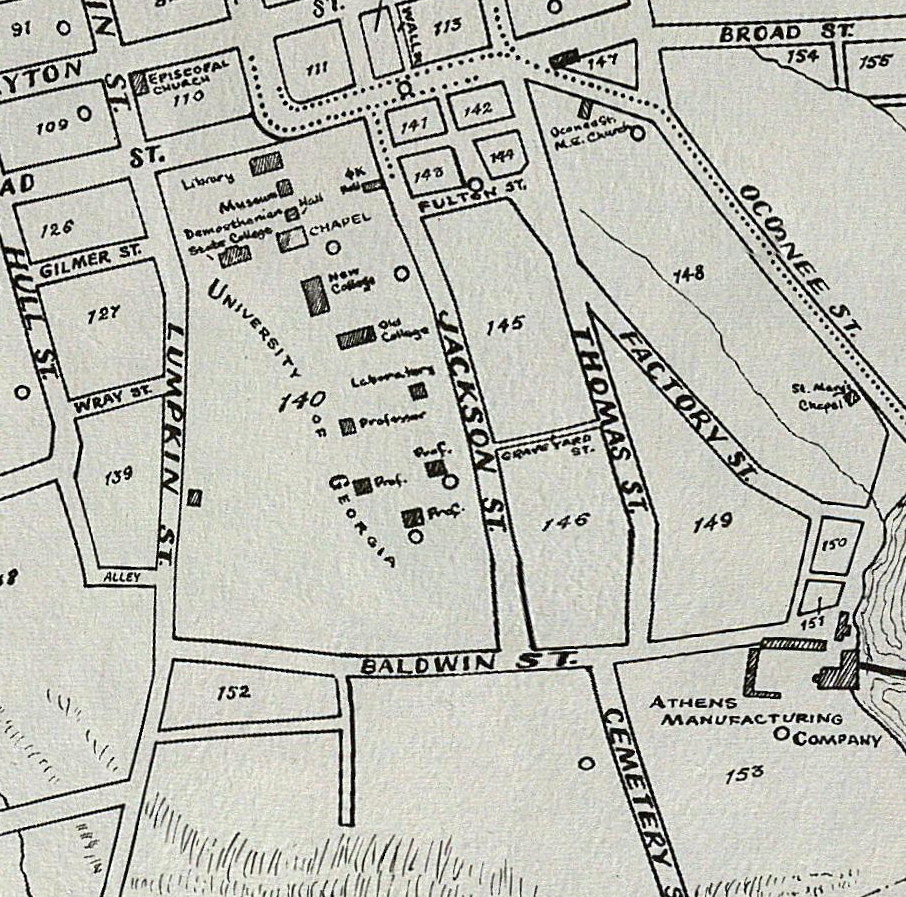

Around 1810 Athenians first began burying their dead on land that would become Old Athens (or Jackson Street) Cemetery. In this early period, the land was in no formal sense a city cemetery; no lots had to be purchased, and neither the city nor the university maintained a record of burials. The ground itself, roughly five acres, had been part of the original university land grant, but the university had, according to tradition (no deed has yet been found), gifted it to the town as a public square. In the 1820s the university donated another acre in recognition of what was already happening: the establishment of a de facto city cemetery.

From the beginning this burying ground was, in a narrow sense, ‘biracial,’ but white Athenians were buried in the more formal and established sections and were allowed to raise markers, while black Athenians were buried in inferior and informal sections and marked with a stone, a wooden cross, or nothing. Given that this “cemetery” once extended six acres and the current boundary has a footprint of two, many of the surrounding roads and buildings are erected on a former graveyard. Even within the narrow confines of the cemetery as now constituted, only 150 of the estimated 800 extant burials have been identified.

As Athens grew, city leaders began to consider the creation of a formal new cemetery, more ordered, less obtrusive, and still convenient to town. Wilson Lumpkin, two-term Georgia governor (and lead architect of the Trail of Tears), had a large plantation south of town, and having recently lost a son—a promising student at UGA—Lumpkin agreed to give seventeen acres to the new cemetery's trustees in exchange for the prime family burial location—the crown of ‘West Hill,’ which would allow him to see his son’s burial marker from his front porch.

Where Jackson Street Cemetery had grown organically, which is to say haphazardly while still reflecting racial norms, Oconee Hill was the work of deeply deliberate choices made by a small white elite. On rolling hills running along the scenic Oconee River, the site was designed as a crown jewel of the rural cemetery movement—a new mortuary aesthetic that reconceived graveyards as landscape parks, sprawling across hills, streams, vistas, and pleasing turns along tree-lined roads, at once capturing the sublimity of nature and the fleetingness of man. For all the illusion of ‘wildness,’ however, the aesthetic was also tightly disciplined—a staging of nature coupled to an assurance that the enormity of mortality would never wholly subsume the stability of class and a (white) man’s claims to granite immortality. A ‘city of the dead,’ Oconee Hill's white families would sleep forever on the best real estate, in private mausoleums and wrought-iron enclosures. Paupers, by contrast, were allowed “the privilege of placing monuments or slabs over these graves—but cannot enclose.” Similarly “a portion of the grounds is allotted for the burial of negroes. Head and foot stones will be allowed but no enclosures.” The ‘portion of the grounds’ allotted to the enslaved were located primarily along the river and in the floodplains; the enslaved would rest eternally at the feet of their former masters.

With Oconee Hill by the 1860s an ordered, ‘city cemetery’ proper, Jackson Street was more than ever left to fend for itself. Both the city and the university acted as if it was the other’s problem, and they were both right. Jackson Street represented an older model for dealing with the dead, a burial commons now past its prime and full to overflowing.

In June 1858, shortly after Oconee Hill opened, the Athens city council tabled its business to hear a complaint from two white residents who claimed that the black section of the old cemetery had become a “nuisance.” The council unanimously resolved “that owing to the crowded and dilapidated condition of the old burying ground for the blacks, of this place, and on account of ample provisions made for them in the grounds of the Oconee Hill Cemetery that after this date there shall be no interments made in the old ground.”

Given the lack of permanent markers in the black section of the cemetery, it makes a sad sort of sense that the lot became gradually overgrown and seemingly abandoned. It is also clear that over the years black and white graves alike were repeatedly disturbed, individually and en masse.

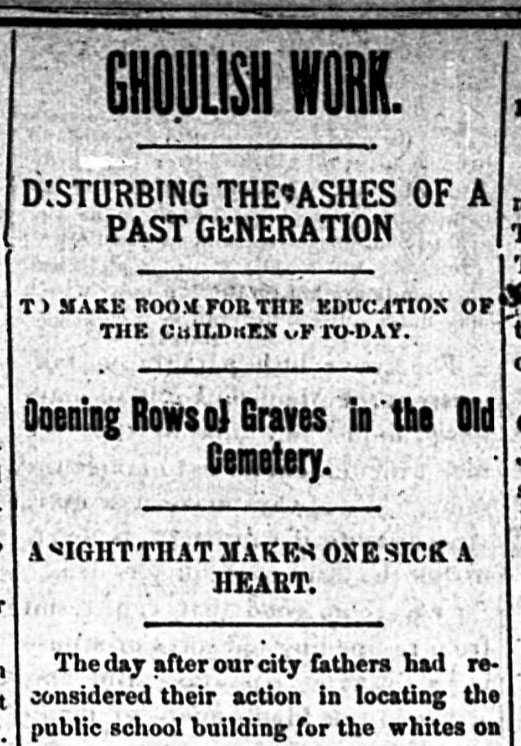

In 1886, under the title “Ghoulish Work,” the Athens Banner-Watchman described a forced work detail uncovering graves while erecting a foundation for a new schoolhouse. The reporter called it “a sight that makes one sick at heart … disturbing the ashes of a past generation to make room for the education of the children of to-day.” (Interestingly the reporter noted that the “spot was an Indian burying ground even before the whites settled here, and the dust of two races of people now mingle in the same soil.” He might have said three.)

“This cemetery once embraced all that land now occupied by the campus,” concluded the reporter. “The street hands while at work frequently excavated human bones, and only a few years ago after a washing rain, we saw an exposed skeleton in a gully. The houses on the campus are built on graves, and the gardens the professors work fertilized by the ashes of a generation long since dead.” “Now that the city has taken possession of this sacred spot of ground,” the reporter concluded, “we think it best that the remains of all the dead be carefully removed, at the city’s expense, to the new cemetery and re-interred there. It is not right that the graves of the dead be made a romping place for school children. It will harden their little hearts and train them up without a proper reverence for the dead. Now that the city has appropriated this property all evidences of its past use should be obliterated.” About this same time, according to later testimony, Professor Robert E. Park was strolling down near the railroad tracks and was surprised to discover that the track cut across the grave plot of his predecessor in the chair of English. Whether the body had been removed is unknown, but supposedly the “Central [railroad] in laying its tracks … was obliged to remove numerous remains to the Oconee Cemetery … and it paid liberally for the work.”

So things went for years. In 1890, the university complained that it was “cramped for space” and tried to reassert title over the cemetery so as to remove the graves (presumably to Oconee Hill), but it was defeated. In the early 1900s road regrade projects, especially on Thomas, discovered graves and pushed them back into the hillside.

The largest disturbance to the cemetery grounds occurred in 1937, when UGA went through a building boom courtesy of the WPA. While readying the foundation for Baldwin Hall, convict laborers purportedly discovered 120 wooden boxes of remains. The best witness we have to this event is the manager of the Georgia Information Service, George M. Battey, who wrote to Duncan Burnet, university Librarian: “As a matter of co-operation, and feeling the Georgia Library should have the information, I take pleasure in sending you with the compliments of the Georgia Information Service, the enclosed matter on the inmates of the old Jackson Street Cemetery in Athens.” Battey’s tone is jovial, almost entirely because he was perfectly confident that the disturbed remains were those of blacks: “The white inmates at the northern end of the cemetery turned over in their graves when they heard picks and shovels digging foundations for a large brick University building in 1938. They rested more easily when it was revealed that the digging was being confined to the southern end where the colored folks of Athens used to be interred; numerous tibias, vertebrae and grinning skulls of colored brothers were unearthed and thrown ‘over the dump,’ while surviving relatives and friends of silent sleepers in this city of the dead shuddered to think of what an extension of building construction would mean.”

It is unclear where ‘over the dump’ precisely was, but probably this means that the bones were pitched over the berm on Thomas Street. The exact movements of the remains thereafter has been the subject of some speculation. Dean Tate, who had been on campus from the early 1920s, remembered that they were ultimately moved to a pauper's ground off Nowhere Road. “During the construction of Baldwin Hall, several unmarked graves of slaves were discovered,” notes a Red & Black article based upon his memory. “These bodies were moved under the direction of Dean Tate to the area where the Athens waterworks are located, and marked with a large monument.” This monument has not been found. The whole process convinced Tate that the entire graveyard should be moved, but he met stiff resistance. “Tate finally got permission to move the bodies,” reported the Red & Black, “but several families stopped him. Tate said some families went so far as to ‘wave guns’ and it was then that the moving was ceased.”

Even as the Jackson Street cemetery—and especially its black section—was being repeatedly disturbed by campus controversy and expansion, Oconee Hill closed its gate to black burials. Precisely when the cemetery became segregated is unknown. The Georgia state legislature passed laws segregating schools in 1872, and towns across Georgia began segregating their cemeteries shortly after. A 1910 edition of the Athens Banner identifies Oconee Hill as the “white cemetery in the city,” and in the same year the Banner ran an article suggesting that living blacks were also unwelcome at Oconee Hill: “The mayor yesterday morning had occasion to try two colored defendants for loitering in Oconee cemetery. The negro man was fined $200 or six months on the gang and the woman with him was assessed $10 or twenty days. The mayor stated that he would break up the practice of negroes loafing in the cemetery. That is sacred ground and its privacy and safety must be protected.” The authorities seemed less worried about the nightly depredations upon the cemetery by university students; in 1938 Frances Barrow remembered that her grandfather, as university chancellor, “would make nightly visits to the cemetery to see that no freshmen had been left tied to tombstones by upperclassmen.” Occasionally, however, the students did commit wholesale vandalism. “Vandalism has always been a problem to the cemeteries and University students are often responsible,” noted the Red & Black. “Dean Tate said three students got drunk one night and pushed over some of the tombstones in Oconee Hills. These students were eventually arrested and sentenced.” One doubts they were sentenced to “six months on the gang,” however.

In 1882, black Athenians founded two burial societies, one on the east side of town—Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery—and one on the west side—Bethlehem (later Brooklyn) Cemetery. Members of these societies typically paid 10 cents a week for burial insurance that secured them a plot and a funeral procession in lodge regalia. Local historian Al Hester has suggested that African Americans flocked to these burial societies not merely because they were being gradually locked out of Oconee Hill but because they were happy, finally, to embrace their own funeral traditions without fear of their bodies being constantly dug up or paved over.

The net effect of black Athenians' move to embrace their own cemeteries was a further erosion of any constituency for Jackson Street. “In the mid 1960s,” noted an article for the Red & Black, “a renovation effort was made to preserve the appearance of the Jackson Cemetery, but today it lies much as it was before the renovation—in a deteriorated state. Dr. Coleman said that when he was a student, there were many more tombstones but over the years, due to vandalism, the stones have disappeared.”

In 1980, the university made a final attempt to solve the problem, announcing the cemetery site as a possible location for a new parking deck. This generated significant backlash, at least among the white community. “With the reaction we got, we heard enough to know it was emotional,” Campus Planning Director William E. Hudson, admitted to the Red & Black. “We’ll just move in other directions. The legal problems are beyond belief. It would have been an extremely costly process to move the cemetery.”

Later that year a group of city residents gathered to form the “Old Athens Cemetery Foundation,” dedicated to preserving the site. “We’d like to see some measures taken so its future is insured,” Foundation president James Reap said. “We won’t go through this thing again.” Informing the university that the “legal problems … would … be stupendous” if it tried to move all the graves, the Foundation offered to take over and beautify the site, as it sat “untended and decimated by years of vandalism and neglect, [littered with] trash and broken glass.” The regents voted on December 9, 1981, to “transfer responsibility for ‘preservation and maintenance’ of the Jackson Street cemetery to the Old Athens Cemetery Foundation,” and the Foundation went to work. By 2002, it had met all of its goals and returned responsibility for maintenance of the cemetery back to the university.

The Present

On November 17, 2015, a construction crew working on the expansion of UGA’s Baldwin Hall uncovered the first of what would prove to be 105 gravesites. According to the early newspaper reports, “the contractor stopped construction work immediately, and contacted the Office of University Architects, who, in turn, contacted the UGA Police Department. UGA Police contacted the Athens-Clarke County Coroner and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, while the Office of University Architects contacted the state Department of Natural Resources and the state archeologist. The GBI took possession of the remains and determined that the area where they were found is not a crime scene.”

As work continued, however, the scope of the problem became clear. Initial reports of ‘several’ gravesites ballooned to several dozen and work was temporarily suspended on December 11. Unlike in 1937, when human remains (at least of African Americans) could be thrown “over the dump,” UGA was in a more precarious position politically though not legally. Legally, it had the right to act, a right it made clear: “According to state law, because it was not a crime scene and an archaeologist determined that the remains were not those of Native Americans, the removal of the remains is up to the landowner [UGA] and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.” The political questions were more sensitive. The town’s right-leaning newspaper supported the university’s contention that the remains were ‘probably’ white. The town’s left-leaning newspaper asked harder questions: Had university administration known that the graves were there to begin with? Had it known that it was constructing on a slave burial ground? Shouldn’t it have known the answers to these questions?

Meanwhile, there were demands the university sponsor DNA tests on the remains to confirm what the black community knew or suspected: these were the remains of formerly enslaved peoples from whom they potentially descended. The university agreed, but the process was slow.

In its initial press release the university had noted that “[b]ased on a visual inspection by the consultant hired to assist the university in this matter, Southeastern Archaeological Services Inc., the remains are believed to be of people of European descent.” What this “visual inspection” was based upon is unknown.

On March 1, 2017, UGA announced that the remains were indeed African American, of an age that suggested they had probably been enslaved, and that the state archaeologist had recommended that they be reinterred in the “same pattern they were found to avoid splitting up families in the nearest cemetery, which happens to be Oconee Hill.” Members of Athens’ black community—especially Fred Smith and Linda Davis—requested that the remains be buried ceremoniously “among their people” in either of the historic black cemeteries. Instead the remains were quickly carried in a Penske truck and buried on the second day of Spring Break behind closed gates at Oconee Hill. Gregory Trevor, spokesman for the university, said “we didn’t want to turn it into a spectacle,” but Fred Smith believes the move was made “to avert blame away from UGA and to provide talking points to senior staff and sympathizers.” For Smith and Davis, the university had reproduced in 2017 a century and a half of similar traumas, where their dead were not respected and their community was not consulted. “I have a belief in my heart that we still live on the University of Georgia plantation,” Linda Davis noted. “They’re being placed close to their white masters again,” Smith said of the remains. “But for us, it’s time to grieve for the girls, boys, women and men abused in life and in death; for the ones removed from the cemetery recently and to who-knows-where in the past; for the ones still buried there; and for them whose remains may have been removed with construction dirt.”

On November 16, 2018, the university dedicated a new memorial to the dead of Baldwin Hall. In his remarks UGA President Jere W. Morehead noted that “the memorial we are dedicating this morning will provide for an enduring tribute as well as a physical space for meaningful reflection.” That ‘meaningful reflection,’ however, did not include a public acknowledgement in any of the official remarks that the people buried under Baldwin Hall were almost certainly enslaved. “The university needs to acknowledge its role in slavery and the ways it continues to uphold white supremacy by not acknowledging that history or making amends for it,” noted District 1 Commissioner Mariah Parker, who joined a group protesting the dedication ceremony. “This gesture, while nice, is not enough. It’s not going to bring justice to the descendants of the folks who are buried here.”

The Future

Acknowledgment is the first step in any truth, reckoning, and reconciliation campaign. While the definitive history of Baldwin Hall remains to be written, the department will continue to research, redraft, and expand this section of the website as new information comes to light. The point is not merely to get the past ‘right,’ but to ask the bigger question of how the past informs the present and helps us build a better future. To that end, the department is engaged in a number of research initiatives designed to write a more inclusive history of our campus, acknowledging alike the people who funded our buildings and built them, acknowledging alike the many ways our curriculum has supported bigotry and broken it down over a two hundred year history. If you would like to contribute to one of our initiatives, please let us know; if you have information that would help us, please be in touch.